2.1 Information Storage

Most computers use block of 8 bits, or bytes, as the smallest unit of memory.

A mechine-level program views memory as a very large array of bytes, referred to as virtual memory. Every byte of memory is identified by a unique nubmer, known as address, and the set of all possible addresses is known as the virtual address space.

Virtual address space is just a conceptual image presented to mechine-level program. The actual implementation uses a combination of DRAM, flash memory, disk storage,special hardware, and operating system software to provide the program with what apears to be a monolithic byte array.

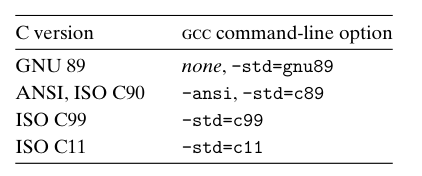

The GNU Compiler Collection (GCC) can compile programs according to the conventions of several different version of the C language, based on different command-line options.

2.1.1 Hexadecimal Notation

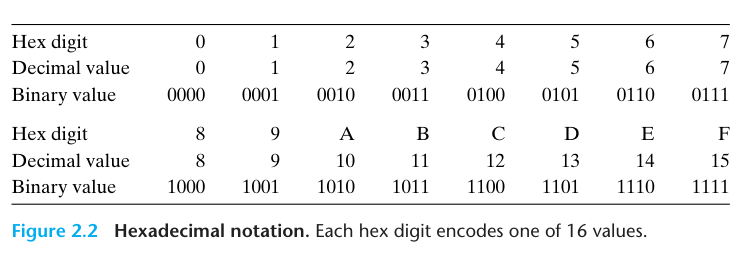

Decimal and binary values associated with the hexadecimal digits:

For $x = 2,048 = 2^{11}$, we have $n = 11 = 3 + 4 \cdot 2$, giving hexdecimal representation 0x800.

2.1.2 Data Sizes

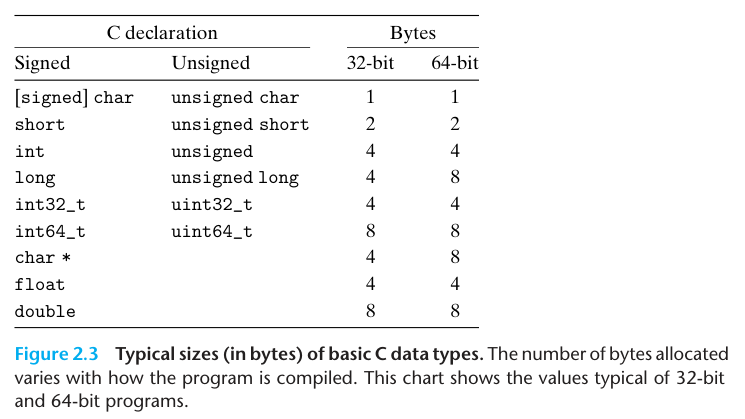

A 32-bit word size limits the virtual address space to 4 gigabytes(written 4 GB), that is, just over 4 x 10^9 bytes. Scaling up to a 64-bit word size leads to a virtual address space of 16 exabytes, or around 1.84 x 10^19 bytes.

The distinction referring to programs as being either “32-bit programs” or “64-bit programs” lies in how a program is compiled, rather than the type of machine on which it runs.

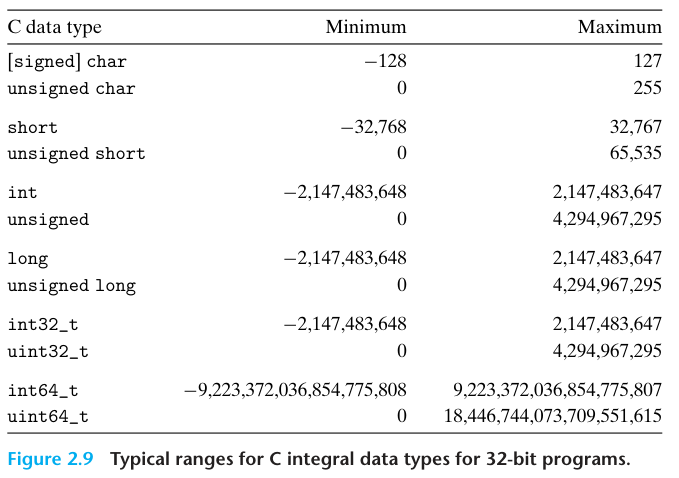

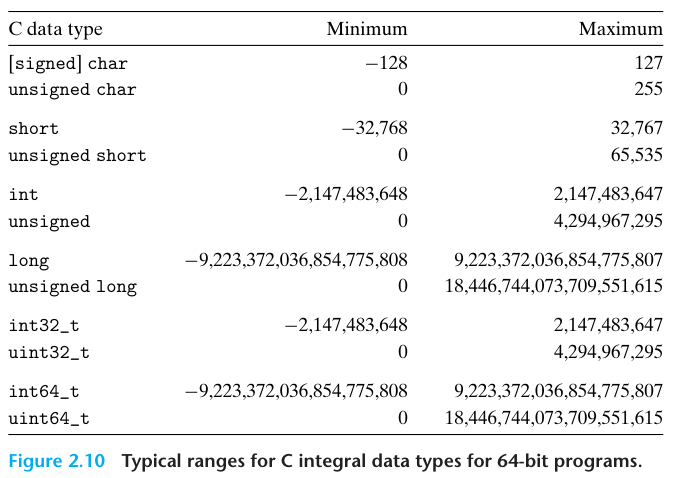

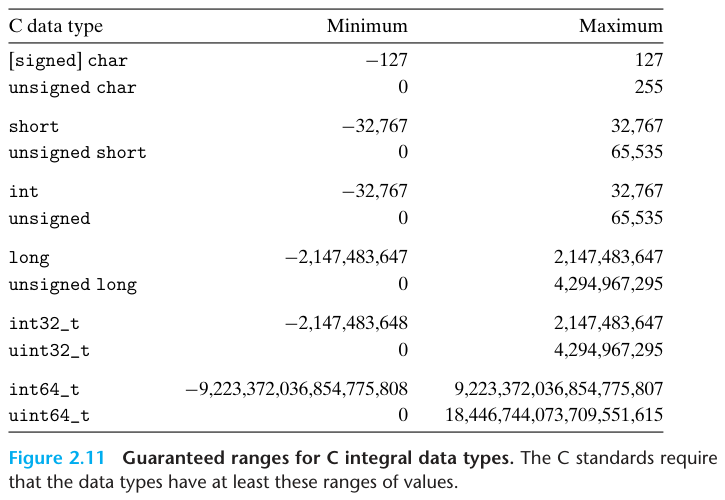

The C language supports multiple data formats for both integer and floating-piont data.

int32_t and int64_t have exactly 4 and 8 bytes, respectively, to avoid the vagaries of relying on “typical” sizes and different compiler settings.

2.1.3 Addressing and Byte Ordering

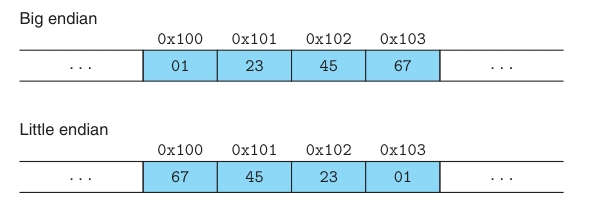

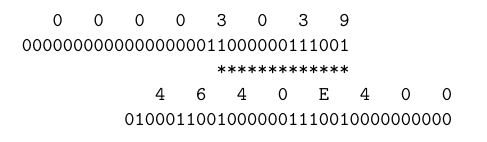

The convention where the least significant bytes comes first is referred to as little endian. The convention where the most sifnificant byte comes first is referred to as big endian.

For value x = 0x01234567, the high-order byte has hexadecimal value 0x01, while the low-order byte has value 0x67.

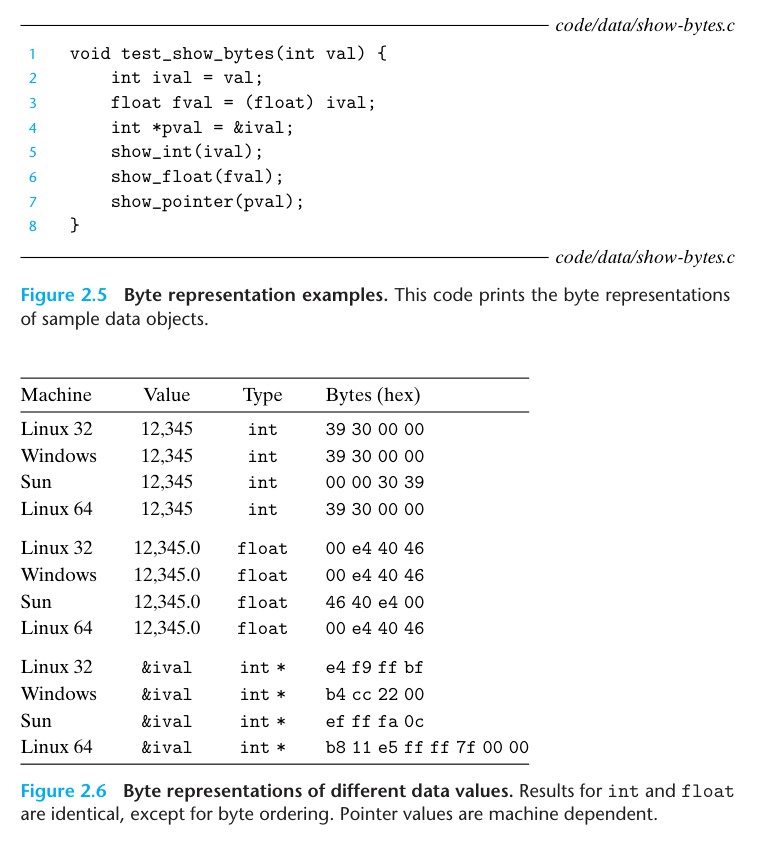

Although the floating-pint and the integer data both encode the numeric value 12,345, they have very different byte patterns: 0x00003039 for the integer and 0x4640E400 for floating point. In general, these two formats use different encoding shemes. If we expand these hexadecimal patterns into binary form and shift them appropriately, we find a sequence of 13 matching bits, indicated by a sequence of asterisks, as follows:

2.1.4 Representing Strings

None

2.1.5 Representing Code

None

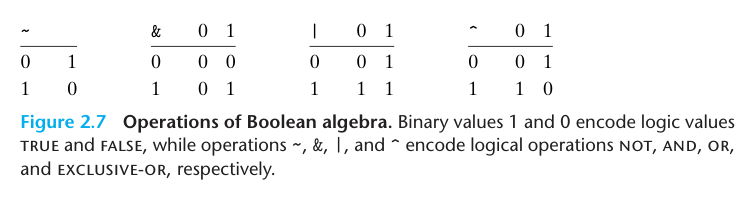

2.1.6 Introduction to Boolean Algebra

When we consider operations ^, & and ~ operating on bit vectors of length w, we get a different mathematical form, known as a Boolean ring.

a ^ a = 0 for any value a, so (a ^ b) ^ a = b.

According to the position of 1 from right to left, bit vector a = [01101001] encodes the set A = {0, 3, 5, 6}, while bit vector b = [01010101] encodes the set B = {0, 2, 4, 6}. Then the operation a & b yields bit vector [01000001], while $A \cap B$ = {0, 6}.

2.1.7 Bit-Level Operations in C

The best way to determin the effect of a bit-level expression is to extend the hexadecimal arguments to their binary representations, perform the operations in binary, and then convert back to the hexadecimal.

A mask is a bit pattern that indicates a selected set of bits within a word. The expression ~0 will yield a mask of all ones.

2.1.8 Logical Operations in C

A bitwise operation will have behavior matching that of its logical counterpart only in the special case in which the arguments are restricted to 0 or 1.

The logical operators do not evaluate their second argument if the result of the expression can be determined by evaluating the first argument.

2.1.9 Shift Operations in C

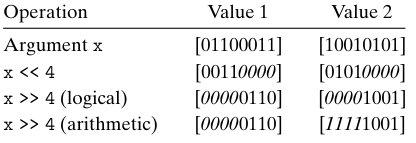

Left shift x << k: $x$ is shifted $k$ bits to the left, dropping off the $k$ most significant bits and filling the right end with $k$ zeros.

Right shift x >> k has:

- Logical. A logical right shift fills the left end with $k$ zeros.

- Arithmetic. An arithemetic right shift fills the left end with $k$ repetitions of the most significant bit.

For signed data (int, long, etc.), it determined by compiler (according to mechine structure) whether right shift in c is logical or arithmetic.

While for unsigned data (unsigned int, unsigned long), it is always logical right shift.

Here are examples:

Arithmetic right shift is the most-used right shift for signed data. But for unsigned data it must be logical right shift.

On many machines, the shift instruction consider only the lower $log_2 w$ bits of the shift amount when shifting a w-bit value, and so the shift amount is computed as k mod w. w is the bit length of the data type. For instance:

| |

2.2 Integer Representations

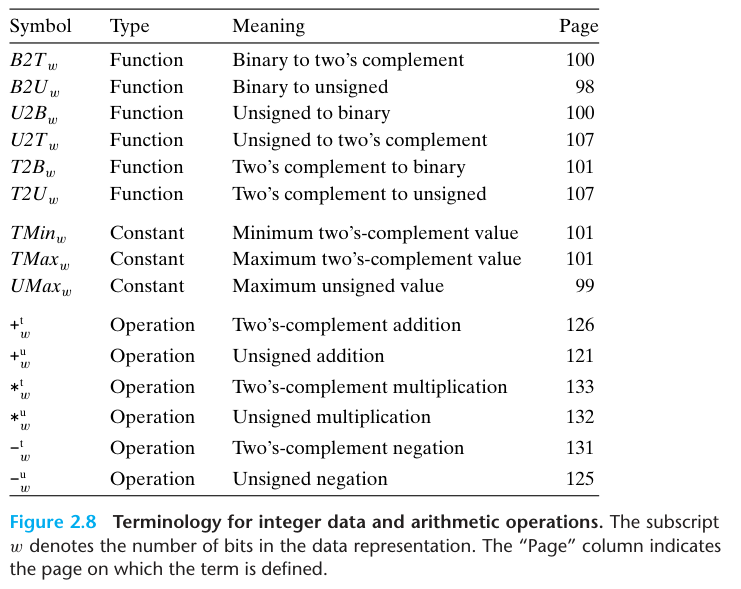

2.2.1 Integral Data Types

2.2.2 Unsigned Encodings

principle: Definition of unsigned encoding

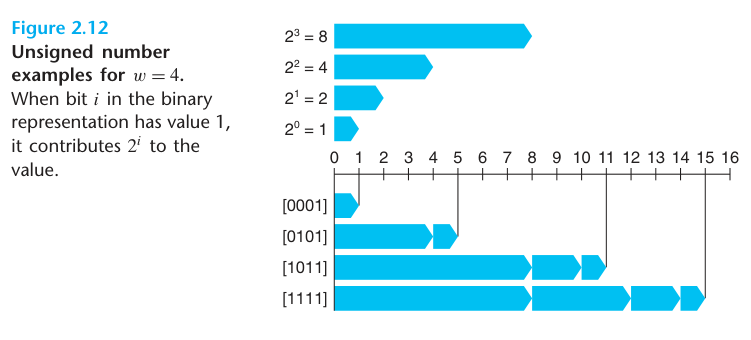

For vector $\vec{x} = [x_{w-1}, x_{w-2}, \ldots, x_{0}$: $$ B2U_{w}(\vec{x}) = \sum_{i=0}^{w-1}x_{i}2^i \qquad (2.1) $$

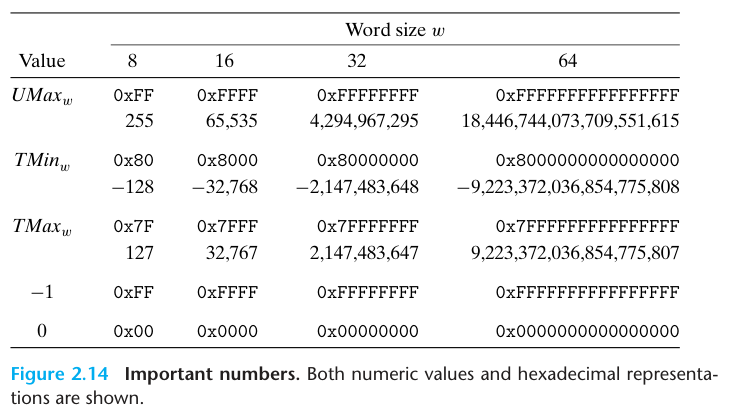

The least value is given by bit vector $[00 \cdots 0]$ having integer value 0, and the greatest value is given by bit vector $[11 \cdots 1]$ having integer value $UMax_{w} \doteq \sum_{i=0}^{w-1}2^i = 2^w - 1$.

principle: Uniqueness of unsigned encoding

Function $B2U_{w}$ is a bijection.

2.2.3 Two’s-Complement Encodings

principle: Definition of two’s-complement encoding

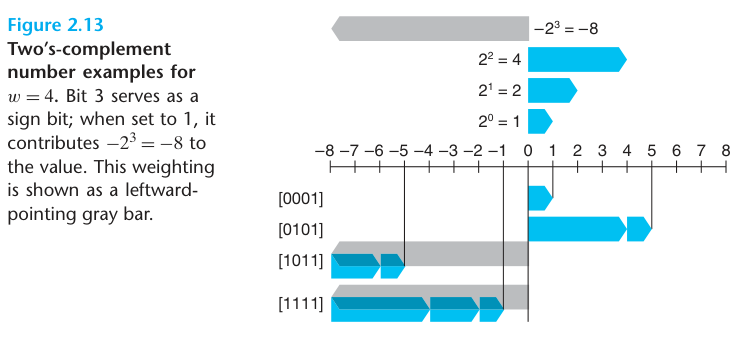

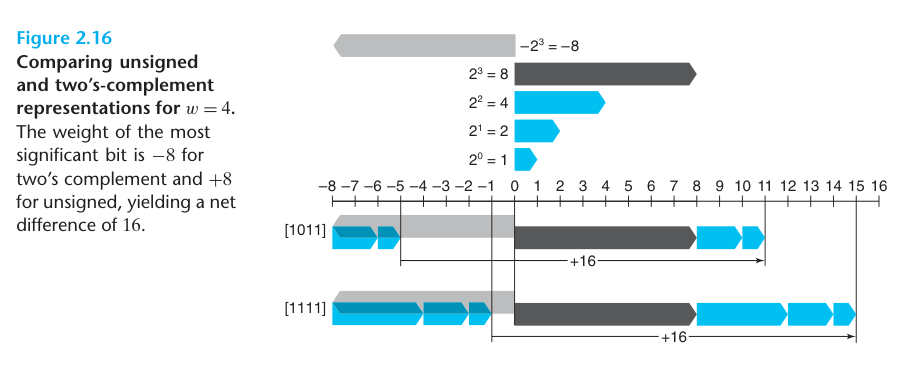

For vector $\vec{x} = [x_{w-1},x_{w-2},\cdots x_{0}]$: $$ B2T_{w}(\vec{x}) \doteq -x_{w-1}2^{w-1} + \sum_{i=0}^{w-2}x_{i}2^{i} \qquad (2.3) $$

The MSB (most significant bit) has its dual role as both the sign and a weighted bit.

The least representable value is given by bitvector [10 ... 0] (set the bit with negative weight but clear all others),having integer value $TMin_{w} \doteq - 2^{w-1}$.The greatest value is given by bitvector [01 ... 1] (clear the bit with negative weight but set all others),having integer value $Tmax_{w} \doteq \sum_{i=0}^{w-2}2^i = 2^{w} - 1$.

principle: Uniqueness of two’s-complement encoding

Function $B2T_{w}$ is a bijection.

$\left| TMin \right| = \left| TMax \right| + 1$

Since 0 is nonnegative, this means that it can represent one less positive number than negative.

Two other standard representations for signed numbers: $$ B2O_{w}(\vec{x}) \doteq -x_{w-1}(2^{w-1} - 1) + \sum {i=0}^{w-2}x{i}2^{i} $$ $$ B2S_{w}(\vec{x}) \doteq (-1)^{x_{w-1}} \cdot \left( \sum {i = 0}^{w-2}x{i}2^{i} \right) $$

2.2.4 Conversions between Signed and Unsigned

$$ T2U_{w}\left( \vec{x} \right) \doteq B2U_{w}\left( T2B_{w} \right) $$ $$ U2T_{w}\left( \vec{x} \right) \doteq B2T_{w}\left( U2B_{w} \right) $$

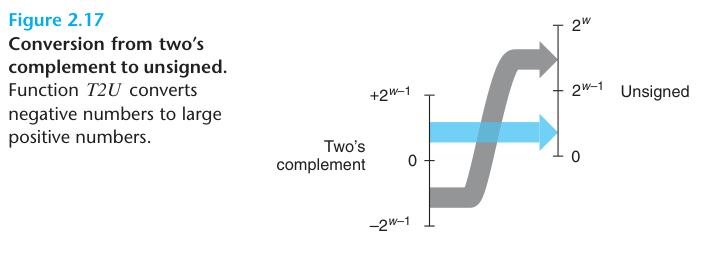

principle: Conversion from two’s complement to unsigned

For x such that $TMinw ≤ x ≤ TMaxw$: $$ T2U_{w}\left( x \right) = \begin{cases} x + 2^{w}, & x < 0 \ x, & x \geq 0 \end{cases} \qquad (2.5) $$

derivation: Conversion from two’s complement to unsigned

Comparing Equations 2.1 and 2.3, we can see that for bit pattern $\vec{x}$, if we compute the difference $B2U_{w}(\vec{x}) - B2T_{w}(\vec{x})$, the weighted sums for bits from 0 to w - 2 will cancel each other, leaving a value $B2U_{w}(\vec{x}) - B2T_{w}(\vec{x}) = x_{w-1} (2^{w-1} - -2^{w-1}) = x_{w-1}2^{w}$. This gives a relationship $B2U_{w}(\vec{x}) = B2T_{w}(\vec{x}) + x_{w-1}2^{w}$. We therefore have

$$

B2U_{w}(T2B_{w}(x)) = T2U_{w}(x) = x ;+;x_{w-1}2^{w} \qquad (2.6)

$$

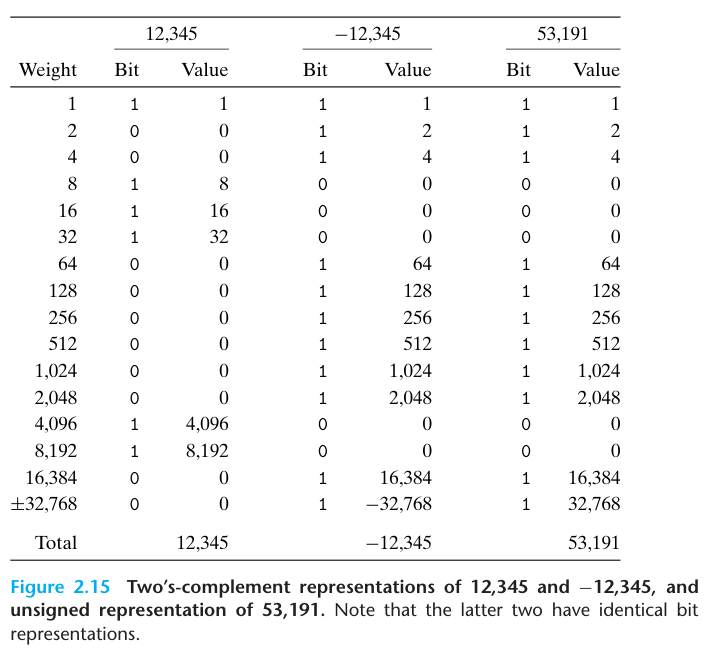

For the two’s-complement case, the most significant bit serves as the sign bit, which we diagram as a leftward-pointing gray bar. For the unsigned case, this bit has positive weight, which we show as a rightward-pointing black bar.

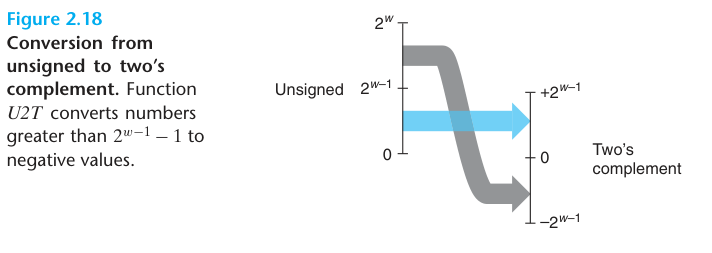

principle: Unsigned to two’s-complement conversion For u such that $0 \leq u \leq UMax_{w}$: $$ U2T_{w}(u) = \begin{cases} u, & u \leq TMax_{w} \ u - 2^{w}, & u > Tmax_{w} \end{cases} \qquad (2.7) $$

derivation: Unsigned to two’s-complement conversion Let $\vec{u} = U2B_{w}(u)$. This bit vector will also be the two’s-complement representation of $U2T_{w}(u)$. Equations 2.1 and 2.3 can be combined to give $$ U2T_{w}(u) = -u_{w-1}2^{w} + u \qquad (2.8) $$

To summarize, we considered the effects of converting in both directions between unsigned and two’s-complement representations. For values x in the range $0 \leq x \leq TMax_{w}$, we have $T2U_{w}(x) = x$ and $U2T_{w}(x) = x$. That is, numbers in this range have identical unsigned and two’s-complement representations. For values outside of this range, the conversions either add or subtract $2^{w}$. For example, we have $T2U_{w}(-1) = -1 + 2^{w}$ -the negative number closest to zero maps to the largest unsigned number. At the other extreme, one can see that $T2U_{w}(TMin_{w}) = -2^{w-1} + 2^{w} = 2^{w-1} = TMax_{w} - 1$ —the most negative number maps to an unsigned number just outside the range of positive two’s-complement numbers. Using the example of Figure 2.15, we can see that $T2U_{16}(-12345) = 65536 + -12345 = 53191$.

2.2.5 Signed versus Unsigned in C

From here on, since repeatedly taking screenshots and copying key words is very troublesome, I will only record key words that help with memory as summarized by myself, which also serves as an index.

most signed by default, suffix u for unsigned

%d, %u, and %x a signed decimal, an unsigned decimal, and in hexadecimal format

possible, print, int with %u, unsigned with %d

result of the expression -1 < 0U is 0 and unsigned, since 0U is unsigned, -1 is implicitly cast to unsigned, which is $T2U_{w}(-1) = UMax_{w} = 4294967295U$.

2.2.6 Expanding the Bit Representation of a Number

unsigned -> large data type => add leading zeros

two’s-complement -> large data type => sign extension (filled by the first bit)

The key property we exploit is that $2^{w} - 2^{w-1} = 2^{w-1}$. Thus, the combined effect of adding a bit of weight $-2^{w}$ and of converting the bit having weight $-2^{w-1}$ to be one with weight $2^{w-1}$ is to preserve the original numeric value.

[[How could the number of bigger data type with leading 1 equals to the original number.en |Here is the chatgpt expalanation of why bigger data type with leading 1 equals to the original number.]]

When short cast to unsigned, it will first promote to int, result in (unsigned)(int) rather than (unsigned)(unsigned short).

2.2.7 Truncating Numbers

| |

[[Why would int 53191 become -12345 after truncating to short.en]]

truncate x down to k bits x': $x’ = x \mod 2^{k}$

[[why does the modula of x mod 2 to k power will retain k bits.en]]

2.2.8 Advice on Signed versus Unsigned

None

2.3 Integer Arithmetic

2.3.2 Two’s-Complement Addition

overflow means remove the most significant bit.

positive overflow: x > 0 & y > 0 but $x +{w}^{t}y \leq 0$. negetive overflow: x < 0 & y < 0 but $x +{w}^{t}y \geq 0$.

$x *{w}^{t} = U2T{w}((x\cdot y)\mod 2^{w})$

k bits will be left if you modula a binary x by k.

we can transform multiplication into shifting, for example, x * 14:

- 14 = 2^3 + 2^2 + 2^1 => (x«3) + (x«2) + (x«1)

- 14 = 2^4 - 2^1 => (x«4) - (x«1)

For the cases where rounding is required, adding the bias causes the upper bits to be incremented, so that the result will be rounded toward zero.

$\lceil x/y \rceil=\lfloor (x + y - 1) / y\rfloor$

c expression that yields x/2^k: (x<0 ? x+(1<<k)-1 : x) >> k

2.4 Floating Point

2.4.1 Fractional Binary Numbers

$$ b = \sum_{i=-n}^{m}2^{i} \times b_{i} $$ it can’t represent a very large number.

2.4.2 IEEE Floating-Point Representation

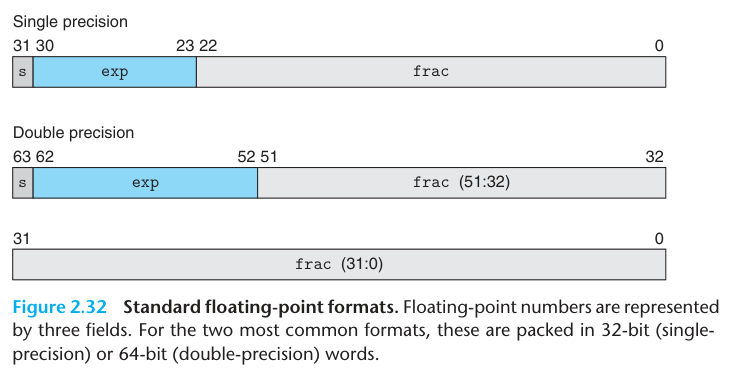

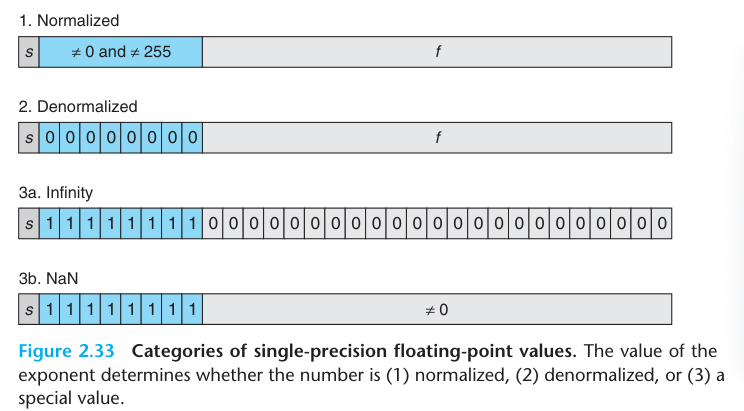

The IEEE floating-point standard represents a number in a form: $V=(-1)^{s}\times M\times2^{E}$.

V: Values s: sign M: significand E: exponent

E = e - bias

2.4.4 Rounding Floating-point

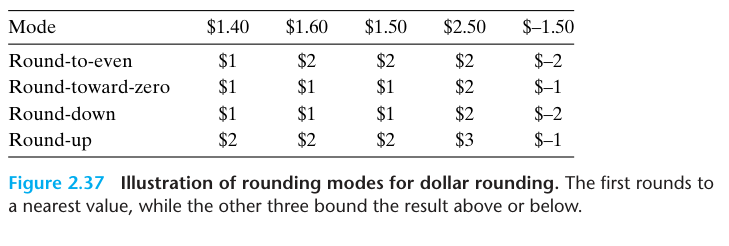

4 rounding modes:

Halfway point format: XX...X.YY...Y100...